Toulmin begins the article by describing previous methods of judiciary practices, where there were no written laws or precedents in Rome for judges to base decisions. Instead, each individual case was handled as a separate, distinct scenario in which all mitigating or unique circumstances were taken into consideration. People trusted the knowledge and discretion of the pontiffs, not an overarching law. But, as Toulmin describes, multiple factors (including immigration that changed societal norms and a need for more and thus less trained judges) constructed a need for established and referable rules which today are the basis for Western judicial systems. This transition is truly a double-edged sword, for now equality and consistency have been established, but in its stead, we sacrifice equity. Simply consider Jean Valjean in Hugo's Les Misérables, who served 19 years (5 for the crime and 14 additional for trying to escape) for

stealing bread to feed his nephew. Did he steal? Yes. Was this crime worthy of 5 years in jail?

To Javert, a servant of God and the Law, there are no mitigating circumstances, a crime is a crime.

And even when the tables turn and Valjean lets Javert escape, Javert is still bent on returning

Valjean to jail. He eventually experiences a mental break where he cannot justify living in a world

where people like Valjean violate his standards of right and wrong.

Philip Quast: Javert's Suicide

The transformation of the judicial system, our reliance on the Constitution and precedent has

emphasized the letter over the spirit of the law, removed wiggle room, and devalued mitigating

circumstances. One need only consider the death of Savita Halappanavar, who died from birth

complications after the abortion she requested was denied. The religious (and in this case Catholic)

view of abortion as wholly wrong contributed to Savita's death, whose health was not a justification

for the abortion. Many anti-choice advocates do allow for abortion in cases of rape, incest, or the

health of the mother, but there are prominent American politicians and even doctors that do not.

In response to Savita's death, Irish politicians are attempting to re-legislate the rules concerning

abortions and when the health of the mother overrides the abortion ban. As Toulmin argues, society

must be wary of an over-reliance on these rules, and must refrain from adjusting laws with more laws,

instead of addressing the morality and ethics of the original law.

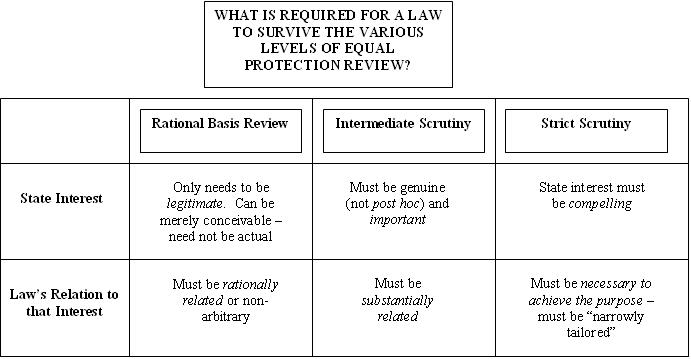

Toulmin's article is a useful transition for me to discuss inherent discrimination and a lack of equity in

the judicial system that I learned about in a fall class. We discussed the different levels of scrutiny that

the courts in America give to different types of discriminatory laws under the equal protection clause.

For example, the strictest level of scrutiny is given to laws based on race and national origin, which is

a prominent reason why many affirmative action cases lose when brought to court, because they treat

people of different races differently. This fact, though in part justified through previous discriminatory

measures that make affirmative action necessary, are not mitigating circumstances. The only way for

racial discrimination of any kind to be allowed through governmental approval is if there is a "compelling

state interest" and the discrimination is the most efficient way to address that interest. A famous example

of this is the Japanese Internment Camps that were ruled constitutional since they did address American

fears over Japanese immigrants during World War II.

|

| Image Retrieved from National Paralegal |

basis review, where discrimination cases based on sexual orientation or mental health are decided.

I find it quite ironic that such levels exist at all. Why are different forms of discrimination created into

a hierarchy of discrimination? Isn't this organization in and of itself discriminatory? It seems to me quite

hypocritical and unjust for someone to receive different punishments or court ruling simply because they

are a different type of bigot than someone else.

I find these different strands inextricably linked. How deeply and strongly do we rely on rules of law, and

for example, these seemingly hypocritical rules, when they lead to death and discrimination? Toulmin argued

that we as a society should not mistake equality for equity, be satisfied with unjust laws, and tie our morality

unquestionably to the rule of law. "We need to recognize that a morality based entirely on general rules and

principles is tyrannical and dis-proportioned, and that only those who make equitable allowances for subtle

individual differences have a proper feeling for the deeper demand of ethics" (p. 107 in Foss's

Readings in Contemporary Rhetoric). I would hope that people would learn to be open-minded towards

people's circumstances, take into account circumstances and mitigation, and let ourselves be human,

reasonable, and overcome our obsession with perfection, black/white dichotomies, and absolutism.